Cornelis Drebbel: The Dutch Alchemist Who Invented the Future

Earlier this year, I was invited to see a wooden submarine — a four-meter replica of Cornelis Drebbel's first functional sub, hidden away in a secret location in Amsterdam. It's a reminder that the most important inventors are often the least remembered.

Drebbel is my favorite Dutch alchemist. He built the first cybernetic system, the first submarine, the first air conditioning, and a clock powered by atmospheric pressure that ran for decades without winding. He influenced Galileo, Francis Bacon, and the founders of the Royal Society. Shakespeare and Ben Jonson wrote plays inspired by his wizardry.

No one knows about him.

His book, De Natura Elementorum, was the first I translated and put online at SourceLibrary.org. This essay is an attempt to restore him to his rightful place in the history of technology.

The Perpetui Mobilis: A Clock That Runs on Air

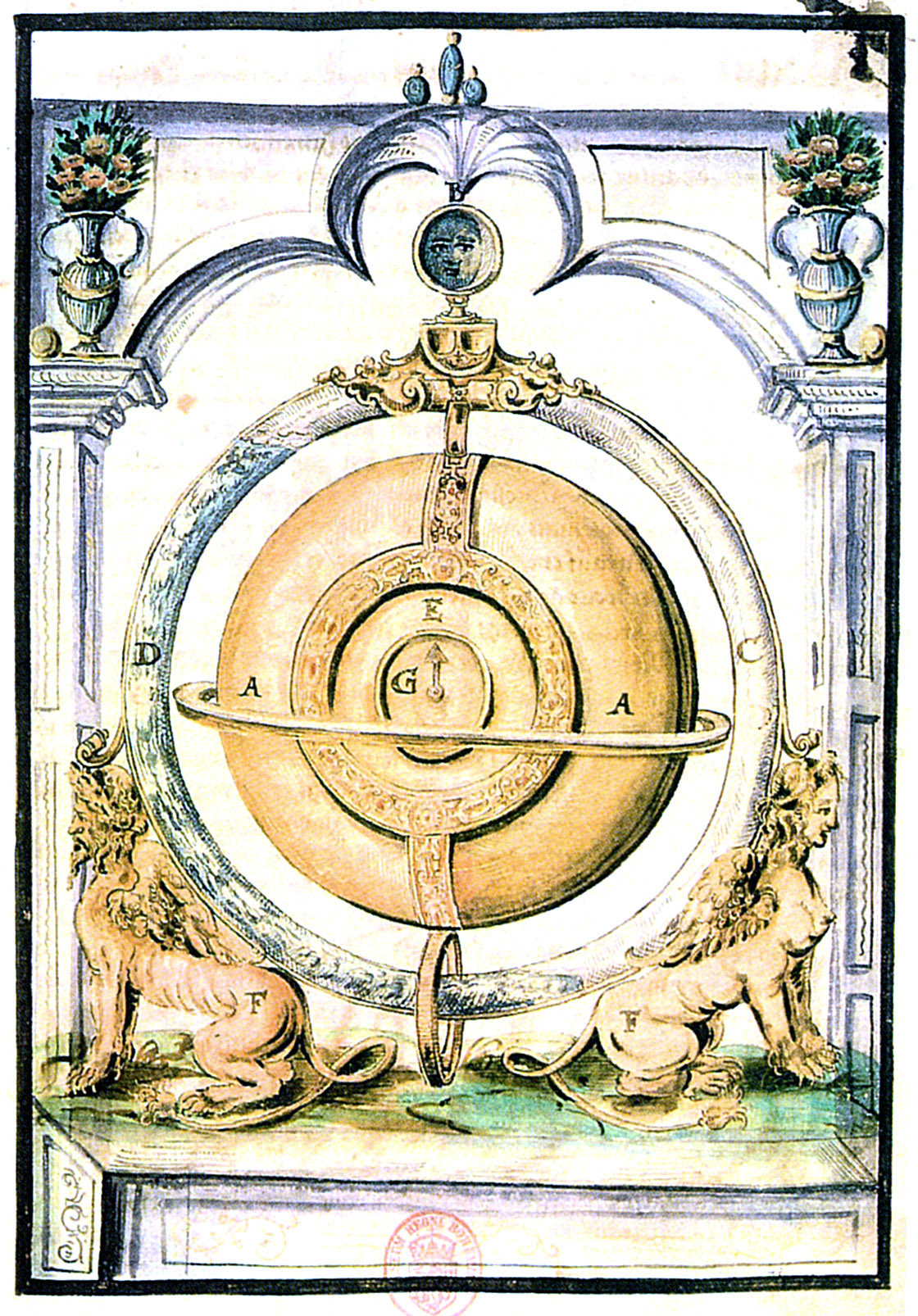

In 1604, Drebbel unveiled what he called the Perpetui Mobilis — and it made him famous across Europe overnight.

The device was an astronomical clock that displayed the date, time, and phases of the moon. It ran without winding, seemingly forever. Contemporary observers were baffled. Drebbel, speaking like the alchemist he was, claimed to have harnessed the "fiery spirit of the air."

We now understand what he discovered: changes in atmospheric pressure and temperature could be converted into mechanical motion. As the air expanded and contracted with daily weather fluctuations, it drove the clock's mechanism. Drebbel had built the ancestor of the modern Atmos clock.

He built as many as eighteen of these devices. The most famous, the Eltham Perpetuum, was made for King James I and became legendary throughout Europe. Another went to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II in Prague.

"Even if the Perpetuum Mobile was only a simple air thermoscope, or at best a crude baroscope, Drebbel invested it with great mystery and great value."

The First Cybernetic System: A Self-Governing Oven

Before Norbert Wiener coined the term "cybernetics" in 1948, before James Watt's steam governor, before any systematic theory of feedback control — there was Drebbel's egg incubator.

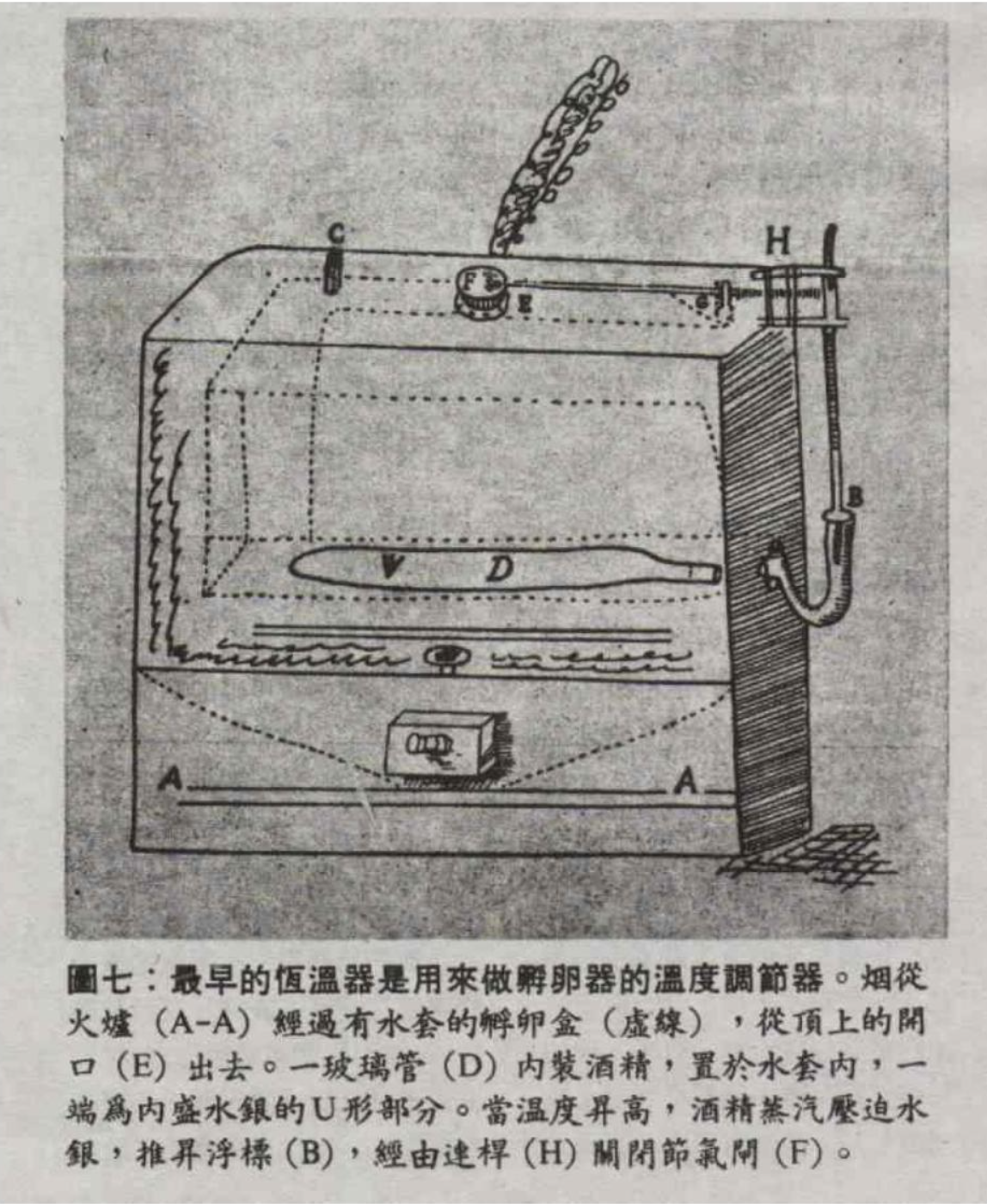

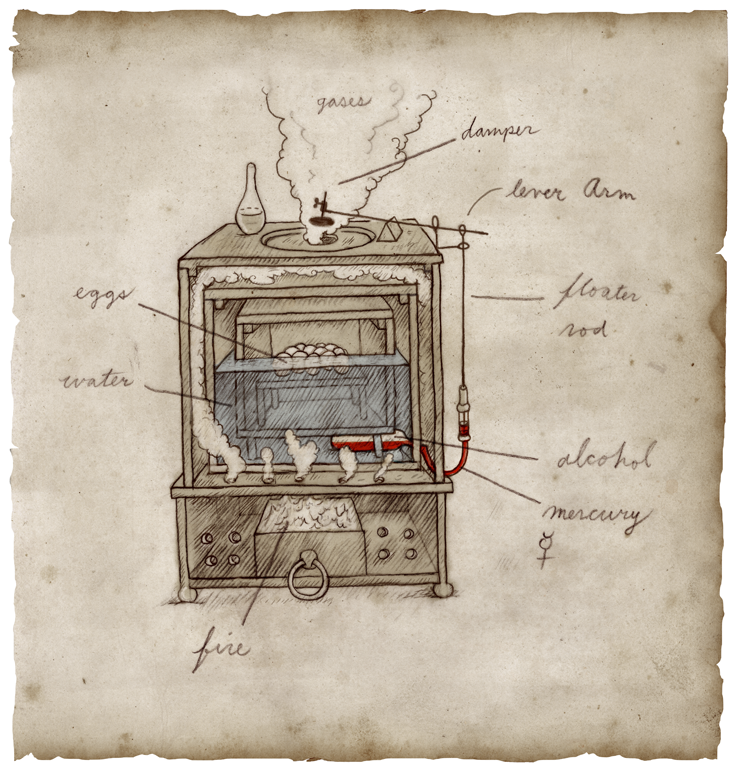

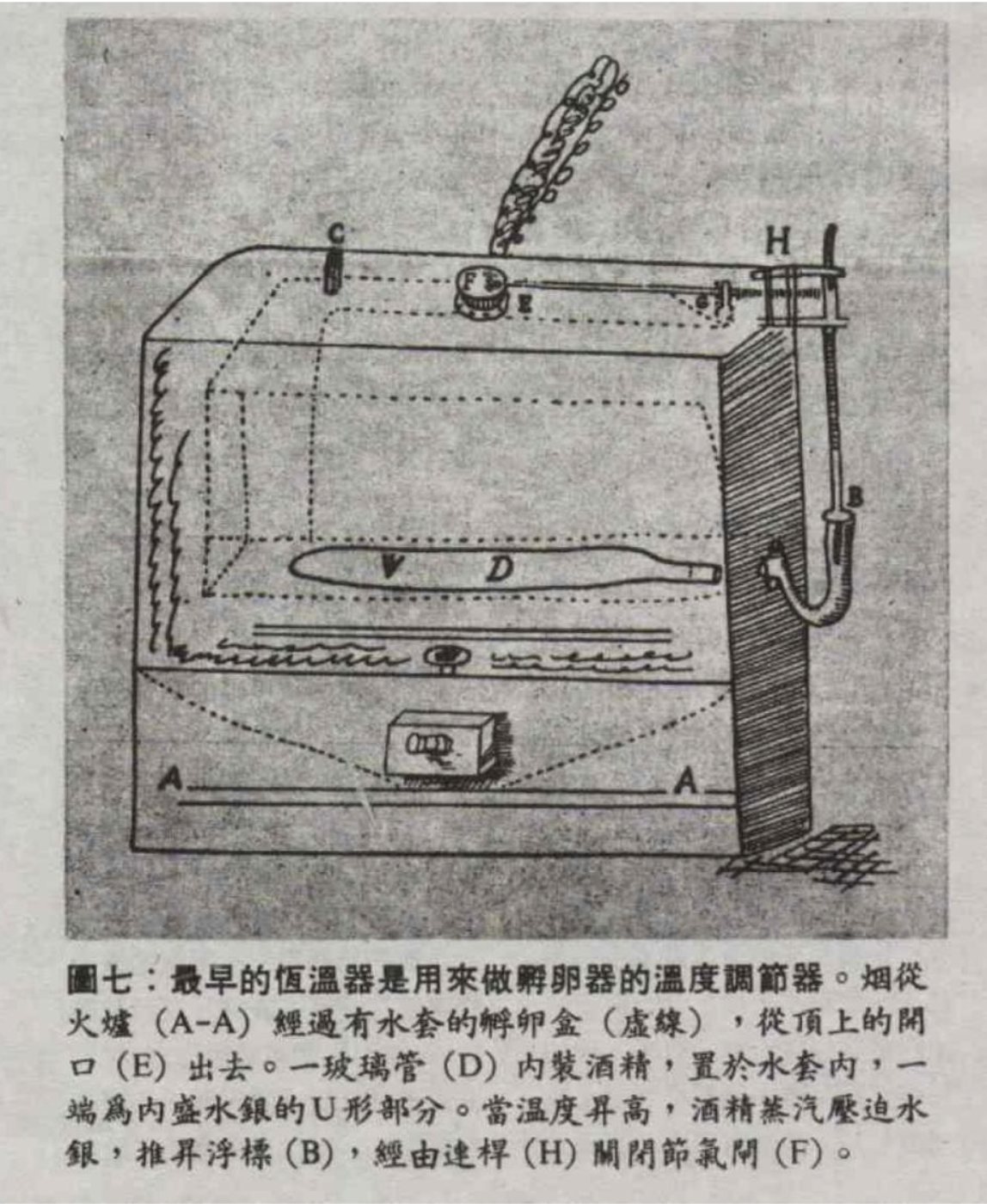

Around 1598, Drebbel patented a self-regulating oven for hatching eggs and drying tobacco. The device maintained a constant temperature without human intervention. It was, as historians of technology have noted, "the first feedback system invented since antiquity."

How did it work? An L-shaped glass tube filled with alcohol and mercury sat inside the oven. A metal rod floated on the mercury. When the temperature rose too high, the expanding alcohol pushed up the mercury, lifting the rod, which lowered a damper to cut off air to the fire. When the oven cooled, the process reversed.

This is the essential logic of all feedback systems: measure the output, compare it to a setpoint, adjust the input. Drebbel had invented the thermostat — and with it, the conceptual foundation for automation itself.

"Drebbel's thermostatic furnace has been called the first feedback system invented since antiquity."

— Encyclopedia.com, "Development of the Self-Regulating Oven"

The Submarine: Sailing Beneath the Thames

Between 1620 and 1624, Drebbel built three increasingly ambitious submarines and tested them in the River Thames. The vessels were wooden frames covered in greased leather, with a watertight hatch, a rudder, and oars.

Dive control was ingenious: large pigskin bladders beneath the rowers' seats were connected to the outside water. To submerge, the crew untied ropes holding the bladders closed, allowing them to fill with water. To surface, they squeezed the bladders flat, expelling the water.

The third and largest model had six oars and could carry sixteen passengers. Drebbel demonstrated it to King James I and thousands of Londoners. The submarine traveled from Westminster to Greenwich and back — a journey of several miles — staying submerged for three hours at depths of 12 to 15 feet.

James I himself went aboard for a test dive, making him the first monarch in history to travel underwater.

THE OXYGEN MYSTERY

How did sixteen people breathe underwater for three hours in a sealed vessel? Drebbel claimed to carry a "quintessence of air" that refreshed the atmosphere inside. Robert Boyle later investigated but could not penetrate the secret. Modern historians believe Drebbel may have generated oxygen by heating saltpeter (potassium nitrate) —150 years before oxygen was officially "discovered."

The First Air Conditioning: Turning Summer into Winter

In the summer of 1620, Drebbel staged another demonstration for King James — this time in Westminster Hall, the largest enclosed space in the British Isles, with a vaulted ceiling stretching 332 feet.

Using troughs filled with snow, water, salt, and potassium nitrate, Drebbel created a zone of frigid air inside the sweltering hall. The chemical mixture drew heat from the surrounding atmosphere — an application of what we now call an endothermic reaction.

The king walked through the chilled zone and, according to accounts, fled shivering from the demonstration. Drebbel had "turned summer into winter" — creating the first documented air conditioning system, three centuries before Willis Carrier.

Lenses, Microscopes, and the Tools of Discovery

Around 1600, Drebbel visited Middelburg, the spectacle-making center of the Netherlands, where he learned lens grinding from Hans Lippershey and Zacharias Janssen — the men credited with inventing the telescope.

With this knowledge, Drebbel developed:

- An automatic lens-grinding machine for precision optics

- A compound microscope with two convex lenses (documented by 1619)

- Improved telescopes using the Keplerian design

- A camera obscura and magic lantern for projecting images

Christiaan Huygens, the great Dutch scientist, credited Drebbel with inventing the compound microscope. In 1624, Galileo saw one of Drebbel's microscopes exhibited in Rome and built his own improved version.

The telescope used by Galileo to discover the moons of Jupiter may have incorporated lenses from Drebbel's workshop — though the exact provenance remains debated by historians.

The Secret of Scarlet: A Chemical Revolution

Like many alchemists, Drebbel worked extensively with colored substances — seeking the Philosopher's Stone, whose production was said to pass through stages marked by color changes.

While making a colored liquid for a thermometer, Drebbel accidentally dropped a flask of aqua regia(a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids) onto a tin windowsill. The tin dissolved into the liquid, and when combined with cochineal dye, it produced a brilliant crimson far more vivid than any red previously known.

Drebbel had discovered the tin mordant — a breakthrough in textile chemistry that would transform the European dye industry. The resulting color, called "Kuffler's color," "Dutch scarlet," or "Bow dye" (after the London workshop his family later established), became the most fashionable red in Europe, reserved for royal cloth.

Wizard of the Stage: Shakespeare, Jonson, and Prospero

Drebbel's inventions made him a valuable asset for the lavish court masques performed for King James. He created special effects — thunder, lightning, storms, and ghostly projections — for the productions of Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare.

He designed mechanical stage props, fountains, and moving figures. His magic lantern projected apparitions onto smoke. His fireworks lit up the night sky. Contemporary audiences saw him as something between an engineer and a sorcerer.

Scholars have suggested that Drebbel inspired the character of Prospero in Shakespeare'sThe Tempest (1611) — the exiled duke who commands spirits and creates storms through his mastery of hidden arts. The play was written during Drebbel's years at the English court, when his fame was at its height.

Ben Jonson satirized the "vulgar mechanick" in his plays, but also relied on his technical genius for the spectacular effects that made the Jacobean masques legendary.

Francis Bacon's Vision: Drebbel and Salomon's House

In 1626, Francis Bacon published New Atlantis, describing a utopian society governed by a research institution called Salomon's House. This fictional academy — often credited as the inspiration for the Royal Society — possessed technologies that read like a catalog of Drebbel's inventions:

- Submarines for underwater exploration

- Cooling chambers for preserving food

- Perpetual motion engines harnessing natural forces

- Optical instruments for extending human vision

The scholar Rosalie Colie demonstrated in her 1955 study that Bacon almost certainly drew on Drebbel's work when imagining the technologies of his ideal society. Drebbel had demonstrated his submarine to James I in 1620; Bacon was at court and knew Drebbel personally.

The founding vision of modern science was shaped, in part, by a Dutch alchemist whom history forgot.

The Royal Society and Robert Boyle

When the Royal Society was founded in 1660, its members knew of Drebbel's work. Robert Boyle — the "father of modern chemistry" — held Drebbel in high esteem, calling him a "deservedly famous mechanician and chymist."

Boyle investigated Drebbel's submarine and tried to understand how the crew had breathed underwater for hours. He could not penetrate the secret, but noted that Drebbel clearly understood something profound about the "complex nature of the atmosphere" — decades before the discovery of oxygen.

Drebbel's work on pneumatics, feedback control, and chemical processes anticipated the research programs that Boyle, Hooke, and their colleagues would pursue at the Royal Society.

Drebbel in the East: Technology Transfer to China and Japan

Drebbel's fame spread far beyond Europe. Through Jesuit missionaries and Dutch trade networks, knowledge of his inventions reached China and Japan in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Qi qi tu shuo ("Illustrations and Explanations of Wonderful Machines"), compiled in 1627 by Jesuit missionary Johann Schreck and Chinese scholar Wang Zheng, introduced Western mechanical technology to China. Telescopes and microscopes possibly made by Drebbel were sold in Rome by his son-in-law Jacob Kuffeler, from where Jesuits brought them to the Chinese court.

Through Rangaku ("Dutch learning"), Japanese scholars in the Edo period studied Western science via Dutch sources at Dejima. Drebbel's thermostat — described as a device that "was not only used for smelting, but also to maintain constant temperature in an incubator" — became known to Japanese natural philosophers.

The Emperor's Alchemist: Prague and Rudolf II

In October 1610, Drebbel and his family traveled to Prague at the invitation of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II — the great patron of alchemy, astronomy, and the occult arts. Rudolf's court was home to Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, and dozens of alchemists seeking the Philosopher's Stone.

Drebbel demonstrated his Perpetui Mobilis, constructed pumps for mining operations, and pursued alchemical research. But when Rudolf was stripped of power by his brother Matthias in 1611, Drebbel was imprisoned for about a year.

After Rudolf's death in 1612, Drebbel was released and returned to London in 1613, where he would spend the rest of his life.

Final Years: The Fens and the Alehouse

Drebbel's final years were marked by declining fortune. By 1630, he was involved in planning the drainage of the Fens around Cambridge — the vast marshlands that would be reclaimed under the direction of the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden.

He died on November 7, 1633, in relative obscurity, running an alehouse in London. The wizard who had entertained kings and inspired utopias ended his days in poverty.

But his legacy endured through his family. His daughters and sons-in-law, the Kufflers, established dye works across Europe using his scarlet recipe. The "Bow dye" remained a family secret for generations.

Why Drebbel Matters: Recovering a Lost Polymath

DREBBEL'S FIRSTS

1598

First thermostat / feedback control system

1604

First atmospheric pressure clock (Perpetui Mobilis)

1619

First compound microscope (documented)

1620

First navigable submarine

1620

First air conditioning demonstration

c.1620

Discovery of tin mordant for scarlet dye

Cornelis Drebbel represents a type of inventor that our modern categories struggle to contain. He was an alchemist who built practical machines. A showman who made genuine discoveries. A court entertainer whose work anticipated cybernetics, submarine warfare, and climate control.

His contemporaries couldn't decide whether he was a genius or a charlatan. He refused to publish his methods, preferring mystery to documentation. He presented himself as a wizard rather than a philosopher — and paid the price in historical memory.

But the evidence of his inventions survives. The testimony of Boyle, Bacon, and Huygens survives. And now, for the first time, his own words are available in English at SourceLibrary.org.

"Public opinion of Drebbel was divided. While some thought of him as a genius inventor, others dismissed him as a mere court entertainer, a dabbler in occultism, and a 'vulgar mechanick' without the right education or scientific rigour."

Four hundred years later, the inventions speak for themselves.

Gallery: The Perpetuum Mobile in 17th-Century Art

Drebbel's Perpetuum Mobile became a status symbol for collectors across Europe. At least thirteen paintings from 1610–1650 depict the device in Kunstkammer (cabinet of curiosities) scenes — a testament to its fame. Peter Paul Rubens himself procured one for the French scholar Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc in 1625.

The Archdukes Albert and Isabella Visiting a Collector's Cabinet

Jan Brueghel the Elder & Hieronymus Francken II, c. 1621–1623

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

The Perpetuum Mobile is visible on the table at left

The Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest

Willem van Haecht, 1628

Rubenshuis, Antwerp

Recently restored; currently on loan at the Prado until Feb 2026

Jan Brueghel the Elder & Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1610–1625

Private collection

One of the earliest depictions

Jan van Kessel the Elder, 1625

Museo del Prado, Madrid

Part of the Five Senses series

Adriaen van Stalbemt, c. 1650

Museo del Prado, Madrid

One of the last depictions in this tradition

Manuscripts & Archives

Drebbel's written legacy survives in scattered archives across Europe and America. The Kuffler family — his sons-in-law and their descendants — preserved many of his secrets and continued his work for generations.

DREBBEL'S WRITINGS

- Een kort Tractaet van de Natuere der Elementen (1621) — Published in Haarlem. The original Dutch treatise on the nature of the elements. PDF at drebbel.net

- Wonder-vondt van de eeuwighe bewegingh (1604/1607) — "Miracle of the eternal movement," describing his Perpetuum Mobile

- De Quinta Essentia (1621) — On the fifth essence, edited by Joachim Morsius. Drebbel's signature appears in Morsius's album amicorum

KUFFLER FAMILY ARCHIVES

- Cambridge University — "A very Good Collection of Approved Receipts of Chymical Operations" (1690), a manuscript by Augustus Kuffler (Drebbel's grandson) with pen and ink diagrams of alchemical processes

- Massachusetts Historical Society — Letters from Abraham Kuffler's brother to John Winthrop, discussing minerals and family affairs

- Carpentras, France — Letters from 1622 describing Drebbel's microscopes

- Calendar of State Papers, Domestic (1661–62) — Petition from Johannes Sibertus Kuffler and Jacob Drebbel requesting £10,000 to demonstrate "their father Cornelius Drebble's secret of sinking or destroying ships in a moment"

- Winthrop Collection — A book annotated: "This was once the booke of that famous philosopher and naturalist, CORNELIUS DREBBEL"

TECHNICAL DRAWINGS OF THE PERPETUUM MOBILE

- John Speed (1604) — Earliest known technical draft

- Heinrich Hiesserle von Chodaw (1607/1612) — Functional description with drawing

- Antonini (1612)

- Thymme (1612)

- William Sanderson, Jakob Fetzer, Joachim Morsius — Various drawings

Sources & Further Reading

- Drebbel, Tractatus Duo: De Natura Elementorum & De Quinta Essentia (1628) — Internet Archive

- Colie, Rosalie. "Cornelis Drebbel and Salomon de Caus: Two Jacobean Models for Salomon's House."Huntington Library Quarterly 18.3 (1955): 245-260.

- "Development of the Self-Regulating Oven" — Encyclopedia.com

- Drebbel.net — Comprehensive archive maintained by Drebbel's descendants

- Britannica: Cornelis Drebbel

- "Cornelis Drebbel's Perpetuum Mobile in the Linder Gallery" — The Mysterious Masterpiece

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Discussion

Loading comments...